TRENDS THAT SHAPED CULTURE: THE MID CENTURY MEDIEVAL MAGIC

Yes, I’m back.

In the world of brands and communication, chasing trends is a national sport. Always on the hunt for the newest, the most relevant, the one that "no one knows about but is going to be big, I swear." Yet, as we constantly search for novelty to present to our dearest clients, we tend to jump from trend to trend and—I've come to realize—only skim the surface. We've reduced trends to empty aesthetics—take Y2K, for instance. Nothing more than pale imitations of a popular look, stripped of the deeper "why" that made them resonate in the first place.

Working with ultra-contemporary trends is incredibly challenging—we're eager to catch them and bend them to our communication needs. But in our rush, we rarely take the time to explore their deeper significance—not just in terms of aesthetics, but, more importantly, their impact on culture and societal behavior.

I believe that only by understanding the history of past trends can we truly grasp their profound impact on society—far beyond meaningless, industrialized aesthetics. To illustrate this, I’ve chosen to explore a trend that echoes one previously discussed in this newsletter: the Medieval Revival. So let’s take a moment to appreciate how trends have the power not just to reflect cultural shifts, but to actively shape them—in aesthetics, art, and social behavior.

An invitation to seize trends for their full potential.

What is the “Mid-Century Medieval Revival” and WHY ON EARTH did the 70s got crazy for the Middle Ages?

The key is: representation.

Ask anyone what comes to mind when they think of the Middle Ages, and chances are words like "violence," "war," "superstition," or even "Dark Ages" will come up. That may be our dominant perception today, but was it the same in the 70s?

During the countercultural movements of the late 60s and the decade that followed, as communities like the hippies emerged, people sought new models and inspirations—ones that broke away from commercial pop culture, mainstream movies, and modern consumerism. They were drawn to ideals that resonated with their own values: psychedelic escapism, honor and belief, community, craftsmanship, and the elevation of the artist’s role in society—rather than just another jukebox full of records to sell.

Luckily for them, they didn’t have to look too far for inspiration. In the 19th century, the Pre-Raphaelite artists had already begun reshaping the way the Middle Ages were imagined. Their work focused on (borderline pagan/mystical) legends, filled with fairies, witches, druids, and love potions, alongside tales of pure, courtly love and quests of honor.

They even redefined the aesthetic of the era. Gone were the high foreheads and odd hats, along with the stern expressions of medieval portraits. Instead, they introduced romanticized scenes, flowing dresses, perfectly cascading hair, and lush, idyllic gardens—shifting the focus from kings and warriors to artists, lovers, and dreamers.

If you were a hippie living in a meadow, believing that love transcends all, the tales of Guinevere and Lancelot or Tristan and Isolde probably struck a chord. Especially if they looked like this:

Add to the mix the rise of Tolkien’s massive popularity by the mid-60s, and you’re pretty much set. Here’s an excerpt from the Tolkien Fandom Wikipedia page, which sums it up perfectly:

So, now let’s dive into the cultural consequences of this medieval fire (the good one I swear).

Music and Songwriting

After the peak of protest folk singing of the 60s, the genre evolved to embrace broadening topics, and musical inspirations.

The Medieval sound of Folk Rock

Musicians gradually began incorporating medieval and Renaissance elements into their music, resurrecting forgotten instruments and techniques, and completely renewing the sound of the decade. Take the flute, for example—the flute solo was the 70s' version of the 80s sax solo. You can hear it in tracks like "Stairway to Heaven" or "Locomotive Breath" (check out the band's outfits, it says it all).

French band Malicorne played over 20 instruments: electric guitars but mostly instruments you probably never heard of (or is it just me?), dulcimer, hurdy gurdy, mandolin, bouzouki, violin, flute, psaltery, or hunting horn. (Btw if you know what instrument she is playing here, please tell me.)

From Singers to Menestrels:

Inspired by Celtic traditions, singers began to perform actual medieval texts, singing about myths, the Arthurian legend, or courtly love. The singer was re-established as a prestigious storyteller, reconnecting with the majestic medieval tradition of poetic songwriting. In the US, Joan Baez interpreted Pauvre Rutebeuf (with music by Leo Ferré), while in France, Tri Yann performed La Complainte de la Blanche Biche (this song is actually from the 16th century, but culture doesn’t care about historians’ dogma). When not singing directly from medieval texts, they invented their own: "Guinnevere" by Crosby, Stills & Nash, "Guinevere" by Donovan (the girl was POPULAR), or even the courtly love story sung by The Rolling Stones in "Lady Jane".

I can't write this without mentioning two of my favorites: Angelo Branduardi’s entire body of work (with La Pulce d’Acqua being one of my childhood treasures) and Leonard Cohen, whose entire discography was studied in an essay called Leonard Cohen: The Modern Troubadour. His tendency to mix religion, spirituality, and contemporary culture, while obsessing over “the unrequited love of the ideal feminine,” made him the perfect heir to the medieval troubadours—those figures embodying the duality of poetry and love, the divine and the profane.

Chivalry Chic: From Mini Skirts to Maxi Dresses

Ok so Substack is telling me I’m soon out of words for this post - so I’ll be shorter.

After the 60s “mini revolution,” long dresses made a surprising comeback, blending medieval shapes with the vibrant colors of the time. Once again, the inspiration came more from the Pre-Raphaelite vision of the Middle Ages than from the actual art of the period. Women were portrayed as romantic figures, with signature flowing hair and comfortable dresses adorned with flower embellishments. Ornamentation made a major return with the hippie movement, drawing parallels with medieval tapestries and their 19th-century heir, the Arts & Crafts movement.

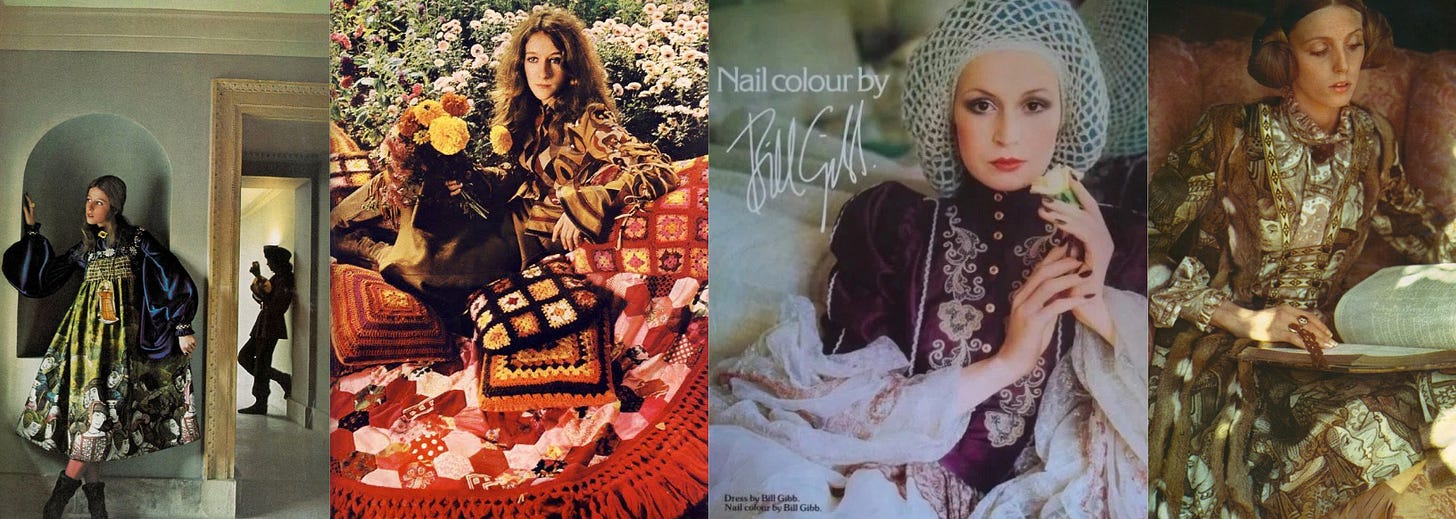

A designer to rediscover, who played a significant role in the medieval revival in fashion, is Bill Gibb, a Scottish designer celebrated for blending traditional handicrafts with inspiration drawn from Medieval and Renaissance paintings. See below:

Today the Mid-Century Medieval Revival is especially being brought from the dead again thanks to its fashion appeal. More and more tiktokers are now producing GRWM about this style:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Knightly Narratives: The Middle Ages on screen

Now, Substack is more and more threatening, so I’ll be super brief, just a few examples

The first Dungeons & Dragons game was out in 1974, just 4 years before the first on screen adaptation of the Lord of the Rings. The dawn of the Fantasy frenzy.

More classic Arthurian adaptations also made a comeback: Perceval by Éric Rohmer (yes, even him) and Excalibur—which actually came out in 1981, but whose entire production took place during the 70s.

The Everyday Medieval

I really wish I could dive deeper into this, but the resources to study are limited, and I don’t have all the time in the world. So here are my instincts about how 70s societal behaviors were influenced by this medieval revival:

The whole new age movement and rise of alternative spiritualities: think of Astrology’s comeback in the 70s inspired by Medieval mysticism.

Natural healing inspired by herbal practices

Furniture and home design, with wood everywhere, the Tudor style retour-en-force…

Communal living: I found this 1970’s New York Times article about communities and their values, emphasizing on the local, community-life, and rejection of the single family units. A reminder of the medieval villages with local governance and shared resources.

My last intuition: Love as a courtly affair. The love depicted in medieval legends is passionate, goes beyond even marital norms, the love in unconditional. Love is broader than two humans, it is a love of community (think of King Arthur and his faithful knights). Love in Medieval legends is a mystic. I read this book last month about catholic mysticsm: the most important text of a Mystic’s bookshelf is the Song of Songs, the erotic poem of the Bible. Yes, in medieval literature love is spiritual. I cannot help myself to relate this vision to post 1969’s society.

At last, could we talk about a new “Mid century medieval revival” today?

My answer is simple: No. Why? Again: representations.

Of course, there is a whole new discourse on medieval aesthetics today, but it is in no way similar to the one of the 70s. Today the medieval representations is much more about violence, women fighters, courage, finding light in darkness, rather than fantasy and Renaissance fairs.

The representation is different, the intention is different and the results: nothing alike.

I must admit, this is why I love studying representations: here, the Middle Ages aren’t just a time period—they’re a fabric to be worn as one desires, a material to create countless iterations from, perfectly tailored for our contemporary needs

I hope that with this post, you will understand how necessary it is to go further than trend-hunting. Let’s do some reaaaal trend-decoding, understanding why people do what they do, why, suddenly, they switch behaviors. Then, maybe, we will accompany people and their present passions, rather than feeding them bland copies.

Leaving you with Education Sentimentale by my favorite French Troubadour, Maxime Le Forestier - with the rose! Was there ever a flower more divine in the Middle Ages? Good job Maxime 🌹